Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Early life and backgroundMohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 in Porbandar, a

coastal town which was then part of the Bombay Presidency, British

India. He was born in his ancestral home, now known as Kirti Mandir,

Porbandar. His father, Karamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), who belonged to

the Hindu Modh community, served as the

diwan (a high official) of Porbander state, a small princely state in the

Kathiawar Agency of British India. His grandfather was Uttamchand

Gandhi, fondly called Utta Gandhi. His mother, Putlibai, who came from

the Hindu Pranami Vaishnava community, was Karamchand's fourth wife, the first three wives having apparently died in childbirth.

[6] Growing up with a devout mother and the Jain

traditions of the region, the young Mohandas absorbed early the

influences that would play an important role in his adult life; these

included compassion for sentient beings, vegetarianism, fasting for

self-purification, and mutual tolerance among individuals of different

creeds.

[7] The Indian classics, especially the stories of Shravana and Maharaja Harishchandra,

had a great impact on Gandhi in his childhood. In his autobiography, he

admits that it left an indelible impression on his mind. He writes: "It

haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without

number." Gandhi's early self-identification with Truth and Love as

supreme values is traceable to these epic characters.

[8][9] In May 1883, the 13-year-old Mohandas was married to 14-year-old Kasturbai Makhanji (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba", and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged child marriage, according to the custom of the region.

[10] Recalling the day of their marriage, he once said, "As we didn't know

much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating

sweets and playing with relatives." However, as was also the custom of

the region, the adolescent bride was to spend much time at her parents'

house, and away from her husband.

In 1885, when Gandhi was 15, the couple's first child was born, but

survived only a few days, and Gandhi's father, Karamchand Gandhi, had

died earlier that year. Mohandas and Kasturba had four more children, all sons: Harilal, born in 1888; Manilal, born in 1892; Ramdas, born in 1897; and Devdas, born in 1900. At his middle school in Porbandar and high school in Rajkot, Gandhi remained an average student. He passed the matriculation exam for Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat, with some difficulty. While there, he was unhappy, in part because his family wanted him to become a barrister.

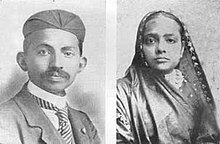

Gandhi and his wife Kasturba (1902)

On 4 September 1888, Gandhi travelled to London, England, to study law at University College London where he studied Indian law and jurisprudence and to train as a barrister at the Inner Temple.

His time in London, the Imperial capital, was influenced by a vow he

had made to his mother in the presence of the Jain monk Becharji, upon

leaving India, to observe the Hindu precepts of abstinence from meat,

alcohol, and promiscuity.

Although Gandhi experimented with adopting "English" customs – taking

dancing lessons for example – he could not stomach the bland vegetarian

food offered by his landlady, and he was always hungry until he found

one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Salt's book, he joined the Vegetarian Society,

was elected to its executive committee, and started a local Bayswater

chapter. Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the

Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original. Not having shown

interest in religion before, he became interested in religious thought

and began to read both Hindu and Christian scriptures.

Gandhi was called to the bar on 10 June 1891. Two days later, he

left London for India, where he learned that his mother had died while

he was in London and that his family had kept the news from him. His

attempts at establishing a law practice in Bombay failed and, later, after applying and being turned down for a part-time job as a high school teacher, he ended up returning to Rajkot

to make a modest living drafting petitions for litigants, a business he

was forced to close when he ran foul of a British officer. In his

autobiography, Gandhi refers to this incident as an unsuccessful attempt

to lobby on behalf of his older brother.

It was in this climate that, in April 1893, he accepted a year-long

contract from Dada Abdulla & Co., an Indian firm, to a post in the Colony of Natal, South Africa, then part of the British Empire.

Civil rights movement in South Africa (1893–1914) Main article: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in South Africa

Gandhi in South Africa (1895)

In South Africa, Gandhi faced the discrimination directed at Indians. He was thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg

after refusing to move from the first-class to a third-class coach

while holding a valid first-class ticket. Travelling farther on by

stagecoach, he was beaten by a driver for refusing to move to make room

for a European passenger.

He suffered other hardships on the journey as well, including being

barred from several hotels. In another incident, the magistrate of a Durban court ordered Gandhi to remove his turban, which he refused to do.

These events were a turning point in Gandhi's life: they shaped his

social activism and awakened him to social injustice. After witnessing

racism, prejudice and injustice against Indians in South Africa, Gandhi began to question his place in society and his people's standing in the British Empire.

M.K. Gandhi while serving in the Ambulance Corps during the Boer War (1899)

M.K. Gandhi while serving in the Ambulance Corps during the Boer War (1899) Gandhi extended his original period of stay in South Africa to assist

Indians in opposing a bill to deny them the right to vote. Though

unable to halt the bill's passage, his campaign was successful in

drawing attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. He

helped found the Natal Indian Congress in 1894,

and through this organisation, he moulded the Indian community of South

Africa into a unified political force. In January 1897, when Gandhi

landed in Durban, a mob of white settlers attacked him and he escaped

only through the efforts of the wife of the police superintendent. He,

however, refused to press charges against any member of the mob, stating

it was one of his principles not to seek redress for a personal wrong

in a court of law.

In 1906, the Transvaal

government promulgated a new Act compelling registration of the

colony's Indian population. At a mass protest meeting held in

Johannesburg on 11 September that year, Gandhi adopted his still

evolving methodology of

satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or non-violent protest, for the first time. He

urged Indians to defy the new law and to suffer the punishments for

doing so. The community adopted this plan, and during the ensuing

seven-year struggle, thousands of Indians were jailed, flogged, or shot

for striking, refusing to register, for burning their registration cards

or engaging in other forms of non-violent resistance. The government

successfully repressed the Indian protesters, but the public outcry over

the harsh treatment of peaceful Indian protesters by the South African

government forced South African General Jan Christiaan Smuts to negotiate a compromise with Gandhi. Gandhi's ideas took shape, and the concept of

satyagraha matured during this struggle.

Accusations of racism Some of Gandhi's South African articles are controversial. On 7 March 1908, Gandhi wrote in the

Indian Opinion of his time in a South African prison: "Kaffirs

are as a rule uncivilised—the convicts even more so. They are

troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals... The kaffirs'

sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife

with and then pass his life in indolence and nakedness. They're

loafers... a species of humanity almost unknown among the Indians."

Writing on the subject of immigration in 1903, Gandhi commented: "We

believe as much in the purity of race as we think they do... We believe

also that the white race in South Africa should be the predominating

race."

During his time in South Africa, Gandhi protested repeatedly about the

social classification of blacks with Indians, whom he described as

"undoubtedly infinitely superior to the Kaffirs". Remarks such as these have led many South Africans to accuse Gandhi of racism.

Two professors of history who specialise in South Africa, Surendra

Bhana and Goolam Vahed, examined this controversy in their text,

The Making of a Political Reformer: Gandhi in South Africa, 1893–1914. (New Delhi: Manohar, 2005). They focus in Chapter 1, "Gandhi, Africans

and Indians in Colonial Natal" on the relationship between the African

and Indian communities under "White rule" and policies which enforced

segregation (and, they argue, led to inevitable conflict between these

communities). Of this relationship, they state that, "the young Gandhi

was influenced by segregationist notions prevalent in the 1890s."

At the same time, they state, "Gandhi's experiences in jail seemed to

make him more sensitive to their plight...the later Gandhi mellowed; he

seemed much less categorical in his expression of prejudice against

Africans, and much more open to seeing points of common cause. His

negative views in the Johannesburg jail were reserved for hardened

African prisoners rather than Africans generally." However, when plans to unveil a statue of Gandhi in Johannesburg were announced, a movement unsuccessfully tried to block it because of Gandhi's racist statements.

Role in Zulu War of 1906 Main article: Bambatha Rebellion

In 1906, after the British introduced a new poll-tax in South Africa, Zulus killed two British officers. In response, the British declared war against the Zulu kingdom.

Gandhi actively encouraged the British to recruit Indians. He argued

that Indians should support the war efforts in order to legitimise their

claims to full citizenship. The British, however, refused to commission

Indians as army officers. Nonetheless, they accepted Gandhi's offer to

let a detachment of Indians volunteer as a stretcher-bearer corps to

treat wounded British soldiers. This corps was commanded by Gandhi. On

21 July 1906, Gandhi wrote in

Indian Opinion:

"The corps had been formed at the instance of the Natal Government by

way of experiment, in connection with the operations against the Natives

consists of twenty three Indians". Gandhi urged the Indian population in South Africa to join the war through his columns in

Indian Opinion:

“If the Government only realised what reserve force is being wasted,

they would make use of it and give Indians the opportunity of a thorough

training for actual warfare.”

In Gandhi's opinion, the Draft Ordinance of 1906 brought the status

of Indians below the level of Natives. He therefore urged Indians to

resist the Ordinance along the lines of

satyagraha by taking the example of "Kaffirs".

In his words, "Even the half-castes and kaffirs, who are less advanced

than we, have resisted the government. The pass law applies to them as

well, but they do not take out passes."

In 1927, Gandhi wrote of the event: "The Boer War

had not brought home to me the horrors of war with anything like the

vividness that the [Zulu] 'rebellion' did. This was no war but a

man-hunt, not only in my opinion, but also in that of many Englishmen

with whom I had occasion to talk."

Struggle for Indian Independence (1915–45) See also: Indian independence movement

In 1915, Gandhi returned from South Africa to live in India. He spoke at the conventions of the Indian National Congress, but was introduced to Indian issues, politics and the Indian people primarily by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a respected leader of the Congress Party at the time.

Role in World War I In April 1918, during the latter part of World War I, the Viceroy

invited Gandhi to a War Conference in Delhi Perhaps to show his support

for the Empire and help his case for India's independence, Gandhi agreed

to actively recruit Indians for the war effort.

In contrast to the Zulu War of 1906 and the outbreak of World War I in

1914, when he recruited volunteers for the Ambulance Corps, this time

Gandhi attempted to recruit combatants. In a June 1918 leaflet entitled

"Appeal for Enlistment", Gandhi wrote "To bring about such a state of

things we should have the ability to defend ourselves, that is, the

ability to bear arms and to use them...If we want to learn the use of

arms with the greatest possible despatch, it is our duty to enlist

ourselves in the army." He did, however, stipulate in a letter to the Viceroy's private secretary that he "personally will not kill or injure anybody, friend or foe."

[33] Gandhi's war recruitment campaign brought into question his consistency on nonviolence as his friend Charlie Andrews

confirms, "Personally I have never been able to reconcile this with his

own conduct in other respects, and it is one of the points where I have

found myself in painful disagreement."

[34] Gandhi's private secretary

also acknowledges that "The question of the consistency between his

creed of 'Ahimsa' (non-violence) and his recruiting campaign was raised

not only then but has been discussed ever since."

Champaran and Kheda Main article: Champaran and Kheda Satyagraha

Gandhi in 1918, at the time of the Kheda and Champaran satyagrahas

Gandhi in 1918, at the time of the Kheda and Champaran satyagrahas Gandhi's first major achievements came in 1918 with the Champaran agitation and

Kheda Satyagraha, although in the latter it was indigo

and other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their

survival. Suppressed by the militias of the landlords (mostly British),

they were given measly compensation, leaving them mired in extreme

poverty. The villages were kept extremely dirty and unhygienic; and

alcoholism was rampant. Now in the throes of a devastating famine, the

British levied a tax which they insisted on increasing. The situation

was desperate. In Kheda in Gujarat, the problem was the same. Gandhi established an ashram

there, organising scores of his veteran supporters and fresh volunteers

from the region. He organised a detailed study and survey of the

villages, accounting for the atrocities and terrible episodes of

suffering, including the general state of degenerate living. Building on

the confidence of villagers, he began leading the clean-up of villages,

building of schools and hospitals and encouraging the village

leadership to undo and condemn many social evils such as untouchability

and alcoholism.

His most important impact came when he was arrested by police on the

charge of creating unrest and was ordered to leave the province.

Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the jail,

police stations and courts demanding his release, which the court

reluctantly granted. Gandhi led organised protests and strikes against

the landlords. With the guidance of the British government, these

landlords agreed to suspend revenue hikes until the famine ended and to

grant the poor farmers of the region increased compensation and control

over farming. It was during this agitation that Gandhi was addressed by

the people as

Bapu (Father) and

Mahatma (Great Soul). In Kheda, Sardar Patel

represented the farmers in negotiations with the British, who suspended

revenue collection and released all the prisoners. As a result, Gandhi

became well known in India.

Non-cooperation Main article: Non-cooperation movement

Gandhi employed non-cooperation, non-violence and peaceful resistance as his "weapons" in the struggle against the British Raj. In Punjab, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of civilians by British troops (also known as the Amritsar Massacre)

caused deep trauma to the nation, leading to increased public anger and

acts of violence. Gandhi criticised both the actions of the British Raj

and the retaliatory violence of Indians. He authored the resolution

offering condolences to British civilian victims and condemning the

riots which, after initial opposition in the party, was accepted

following Gandhi's emotional speech advocating his principle that all

violence was evil and could not be justified.

After the massacre and subsequent violence, Gandhi began to focus on

winning complete self-government and control of all Indian government

institutions, maturing soon into

Swaraj or complete individual, spiritual, political independence.

Mahatma Gandhi's room at Sabarmati Ashram

Sabarmati Ashram, Gandhi's home in Gujarat

Sabarmati Ashram, Gandhi's home in Gujarat In December 1921, Gandhi was invested with executive authority on behalf of the Indian National Congress. Under his leadership, the Congress was reorganised with a new constitution, with the goal of

Swaraj.

Membership in the party was opened to anyone prepared to pay a token

fee. A hierarchy of committees was set up to improve discipline,

transforming the party from an elite organisation to one of mass

national appeal. Gandhi expanded his non-violence platform to include

the

swadeshi policy – the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. Linked to this was his advocacy that

khadi (homespun cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made

textiles. Gandhi exhorted Indian men and women, rich or poor, to spend

time each day spinning

khadi in support of the independence movement.

[36] Gandhi even invented a small, portable spinning wheel that could be folded into the size of a small typewriter.

[37] This was a strategy to inculcate discipline and dedication to weeding

out the unwilling and ambitious and to include women in the movement at a

time when many thought that such activities were not respectable

activities for women. In addition to boycotting British products, Gandhi

urged the people to boycott British educational institutions and law

courts, to resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honours.

An example demonstrates popularity of Gandhi, importance of

participation of people in the freedom movement and Gandhi's words on

worth of sacrifice. While he was popularising Khadi in rural Orissa,

an aged poor woman who was listening to a speech by Gandhi fought her

way to where he was, touched his feet and put a one-paise copper coin in

front of him. Gandhi accepted the coin and thanked her. He said to Jamnalal Bajaj about it as:

"This coin was perhaps all that the poor woman possessed. She gave

me all she had. That was very generous of her. What a great sacrifice

she made. That is why I value this copper coin more than a crore of

rupees."

"Non-cooperation" enjoyed widespread appeal and success, increasing

excitement and participation from all strata of Indian society. Yet,

just as the movement reached its apex, it ended abruptly as a result of a

violent clash in the town of Chauri Chaura,

Uttar Pradesh, in February 1922. Fearing that the movement was about to

take a turn towards violence, and convinced that this would be the

undoing of all his work, Gandhi called off the campaign of mass civil

disobedience. According to Andrew Roberts,

this was the third time that Gandhi had called off a major campaign,

"leaving in the lurch more than 15,000 supporters who were jailed for

the cause".

Gandhi was arrested on 10 March 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced

to six years' imprisonment. He began his sentence on 18 March 1922. He

was released in February 1924 for an appendicitis operation, having served only 2 years.

Without Gandhi's unifying personality, the Indian National Congress

began to splinter during his years in prison, splitting into two

factions, one led by Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru favouring party participation in the legislatures, and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel,

opposing this move. Furthermore, cooperation among Hindus and Muslims,

which had been strong at the height of the non-violence campaign, was

breaking down. Gandhi attempted to bridge these differences through many

means, including a three-week fast in the autumn of 1924, but with

limited success.

[41] This may have been due to Gandhi's "uncanny ability to irritate and frustrate" India's Muslim leadership.

[40] Salt Satyagraha (Salt March) Main article: Salt Satyagraha

Gandhi at Dandi, 5 April 1930, at the end of the Salt March

Gandhi at Dandi, 5 April 1930, at the end of the Salt March Gandhi stayed out of active politics and, as such, the limelight for

most of the 1920s. He focused instead on resolving the wedge between the

Swaraj Party and the Indian National Congress, and expanding

initiatives against untouchability, alcoholism, ignorance and poverty.

He returned to the fore in 1928. In the preceding year, the British

government had appointed a new constitutional reform commission under

Sir John Simon, which did not include any Indian as its member. The

result was a boycott of the commission by Indian political parties.

Gandhi pushed through a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December

1928 calling on the British government to grant India dominion status or

face a new campaign of non-cooperation with complete independence for

the country as its goal. Gandhi had not only moderated the views of

younger men like Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru, who sought a

demand for immediate independence, but also reduced his own call to a

one year wait, instead of two. The British did not respond. On 31

December 1929, the flag of India was unfurled in Lahore.

26 January 1930 was celebrated as India's Independence Day by the

Indian National Congress meeting in Lahore. This day was commemorated by

almost every other Indian organisation. Gandhi then launched a new

satyagraha against the tax on salt in March 1930. This was highlighted

by the famous Salt March to Dandi from 12 March to 6 April, where he

marched 388 kilometres (241 mi) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make

salt himself. Thousands of Indians joined him on this march to the sea.

This campaign was one of his most successful at upsetting British hold

on India; Britain responded by imprisoning over 60,000 people.

The government, represented by Lord Edward Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi–Irwin Pact

was signed in March 1931. The British Government agreed to free all

political prisoners, in return for the suspension of the civil

disobedience movement. Also as a result of the pact, Gandhi was invited

to attend the Round Table Conference in London as the sole

representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference was a

disappointment to Gandhi and the nationalists, because it focused on the

Indian princes and Indian minorities rather than on a transfer of

power. Furthermore, Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon,

began a new campaign of controlling and subduing the nationalist

movement. Gandhi was again arrested, and the government tried to negate

his influence by completely isolating him from his followers. But this

tactic failed.

Mahadev Desai (left) reading out a letter to Gandhi from the viceroy at Birla House, Bombay, 7 April 1939

Mahadev Desai (left) reading out a letter to Gandhi from the viceroy at Birla House, Bombay, 7 April 1939 In 1932, through the campaigning of the Dalit leader B. R. Ambedkar,

the government granted untouchables separate electorates under the new

constitution. In protest, Gandhi embarked on a six-day fast in September

1932. The resulting public outcry successfully forced the government to

adopt an equitable arrangement through negotiations mediated by Palwankar Baloo.

This was the start of a new campaign by Gandhi to improve the lives of

the untouchables, whom he named Harijans, the children of God.

On 8 May 1933, Gandhi began a 21-day fast of self-purification to

help the Harijan movement. This new campaign was not universally

embraced within the Dalit community, as prominent leader B. R. Ambedkar condemned Gandhi's use of the term

Harijans as saying that Dalits were socially immature, and that privileged caste

Indians played a paternalistic role. Ambedkar and his allies also felt

Gandhi was undermining Dalit political rights. Gandhi had also refused

to support the untouchables in 1924–25 when they were campaigning for

the right to pray in temples. Because of Gandhi's actions, Ambedkar

described him as "devious and untrustworthy". Gandhi, although born into the Vaishya caste, insisted that he was able to speak on behalf of Dalits, despite the presence of Dalit activists such as Ambedkar.

In the summer of 1934, three unsuccessful attempts were made on Gandhi's life.

When the Congress Party chose to contest elections and accept power

under the Federation scheme, Gandhi resigned from party membership. He

did not disagree with the party's move, but felt that if he resigned,

his popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's

membership, which actually varied, including communists, socialists,

trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, and those with

pro-business convictions, and that these various voices would get a

chance to make themselves heard. Gandhi also wanted to avoid being a

target for Raj propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily

accepted political accommodation with the Raj.

[44] Gandhi returned to active politics again in 1936, with the Nehru

presidency and the Lucknow session of the Congress. Although Gandhi

wanted a total focus on the task of winning independence and not

speculation about India's future, he did not restrain the Congress from

adopting socialism as its goal. Gandhi had a clash with Subhas Bose, who had been elected president in 1938. Their main points of contention were Bose's lack of commitment to democracy

[citation needed] and lack of faith in non-violence. Bose won his second term despite

Gandhi's criticism, but left the Congress when the All-India leaders

resigned en masse in protest of his abandonment of the principles

introduced by Gandhi.

World War II and Quit India Main article: Quit India Movement

Jawaharlal Nehru sitting next to Gandhi at the AICC General Session, 1942

Jawaharlal Nehru sitting next to Gandhi at the AICC General Session, 1942 World War II broke out in 1939 when Nazi Germany invaded Poland.

Initially, Gandhi favoured offering "non-violent moral support" to the

British effort, but other Congressional leaders were offended by the

unilateral inclusion of India in the war, without consultation of the

people's representatives. All Congressmen resigned from office.

After long deliberations, Gandhi declared that India could not be party

to a war ostensibly being fought for democratic freedom, while that

freedom was denied to India itself. As the war progressed, Gandhi

intensified his demand for independence, drafting a resolution calling

for the British to

Quit India. This was Gandhi's and the Congress Party's most definitive revolt aimed at securing the British exit from India.

Gandhi was criticised by some Congress party members and other Indian

political groups, both pro-British and anti-British. Some felt that not

supporting Britain more in its struggle against Nazi Germany was

unethical. Others felt that Gandhi's refusal for India to participate in

the war was insufficient and more direct opposition should be taken,

while Britain fought against Nazism yet continued to contradict itself

by refusing to grant India Independence.

Quit India became the most forceful movement in the history of the struggle, with mass arrests and violence on an unprecedented scale.

Thousands of freedom fighters were killed or injured by police gunfire,

and hundreds of thousands were arrested. Gandhi and his supporters made

it clear they would not support the war effort unless India were

granted immediate independence. He even clarified that this time the

movement would not be stopped if individual acts of violence were

committed, saying that the

"ordered anarchy" around him was

"worse than real anarchy." He called on all Congressmen and Indians to maintain discipline via ahimsa, and

Karo Ya Maro ("Do or Die") in the cause of ultimate freedom.

"I want world sympathy in this battle of right against might" – Dandi 5 April 1930

Gandhi and the entire Congress Working Committee were arrested in Bombay by the British on 9 August 1942. Gandhi was held for two years in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. It was here that Gandhi suffered two terrible blows in his personal life. His 50-year old secretary Mahadev Desai

died of a heart attack 6 days later and his wife Kasturba died after 18

months imprisonment on 22 February 1944; six weeks later Gandhi

suffered a severe malaria

attack. He was released before the end of the war on 6 May 1944 because

of his failing health and necessary surgery; the Raj did not want him

to die in prison and enrage the nation. He came out of detention to an

altered political scene – the Muslim League for example, which a few years earlier had appeared marginal, "now occupied the centre of the political stage"

and the topic of Jinnah's campaign for Pakistan was a major talking

point. Gandhi met Jinnah in September 1944 in Bombay but Jinnah

rejected, on the grounds that it fell short of a fully independent

Pakistan, his proposal of the right of Muslim provinces to opt out of

substantial parts of the forthcoming political union.

Although the Quit India movement had moderate success in its objective, the ruthless suppression of the movement

[clarification needed] brought order to India by the end of 1943. At the end of the war, the

British gave clear indications that power would be transferred to Indian

hands. At this point Gandhi called off the struggle, and around 100,000

political prisoners were released, including the Congress's leadership.

Partition of India See also: Partition of India

While the Indian National Congress and Gandhi called for the British to quit India, the Muslim League passed a resolution for them to divide and quit, in 1943.

[50] Gandhi is believed to have been opposed to the partition during

independence and suggested an agreement which required the Congress and

Muslim League to cooperate and attain independence under a provisional

government, thereafter, the question of partition could be resolved by a

plebiscite in the districts with a Muslim majority.

[51] When Jinnah called for Direct Action,

on 16 August 1946, Gandhi was infuriated and visited the most riot

prone areas to stop the massacres, personally. He made strong efforts to

unite the Indian Hindus, Muslims and Christians and struggled for the

emancipation of the "untouchables" in Hindu society.

On the 14 and 15 August 1947 the Indian Independence Act was invoked and the following carnage witnessed a displacement of up to 12.5 million people in the former British Indian Empire with an estimated loss of life varying from several hundred thousand to a million.

But for his teachings, the efforts of his followers, and his own

presence, there would have been much more bloodshed during the

partition, according to prominent Norwegian historian, Jens Arup Seip.

Stanley Wolpert's words sum up Gandhi's role and views on the partition perfectly:

Assassination See also: Assassination of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

Raj Ghat, Delhi is a memorial to Mahatma Gandhi that marks the spot of his cremation

Raj Ghat, Delhi is a memorial to Mahatma Gandhi that marks the spot of his cremation

Gandhi's ashes at Aga Khan Palace (Pune, India) On 30 January 1948, Gandhi was shot while he was walking to a

platform from which he was to address a prayer meeting. The assassin, Nathuram Godse, was a Hindu nationalist with links to the extremist Hindu Mahasabha, who held Gandhi responsible for weakening India by insisting upon a payment to Pakistan.

[56] Godse and his co-conspirator Narayan Apte were later tried and convicted; they were executed on 15 November 1949. Gandhi's memorial (or

Samādhi) at Rāj Ghāt, New Delhi, bears the epigraph "Hē Ram", (Devanagari:

हे ! राम or,

He Rām),

which may be translated as "Oh God". These are widely believed to be

Gandhi's last words after he was shot, though the veracity of this

statement has been disputed.

[57] Jawaharlal Nehru addressed the nation through radio:

[58]

"Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there

is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how

to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the

nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we

will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we

will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a

terrible blow, not only for me, but for millions and millions in this

country." – Jawaharlal Nehru's address to Gandhi

Gandhi's ashes were poured into urns which were sent across India for memorial services. Most were immersed at the Sangam at Allahabad on 12 February 1948, but some were secretly taken away.

[59] In 1997, Tushar Gandhi immersed the contents of one urn, found in a bank vault and reclaimed through the courts, at the Sangam at Allahabad.

[59][60] Some of Gandhi's ashes were scattered at the source of the Nile River

near Jinja, Uganda, and a memorial plaque marks the event. On 30 January

2008, the contents of another urn were immersed at Girgaum Chowpatty by the family after a Dubai-based businessman had sent it to a Mumbai museum.

[59] Another urn has ended up in a palace of the Aga Khan in Pune

[59] (where he had been imprisoned from 1942 to 1944) and another in the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine in Los Angeles.

[61] The family is aware that these enshrined ashes could be misused for

political purposes, but does not want to have them removed because it

would entail breaking the shrines.

[59]